Cartilaginous Fish

The gnathostome lineage that produced cartilaginous fish diverged from the bony fish lineage shortly after the placoderm lineage diverged. Sharks have always been the major type of cartilaginous fish and have undergone two great adaptive radiations, the first of which occurred in the Silurian and Devonian Periods. ecause the skeleton of cartilaginous fish is cartilage instead of bone, their teeth are the most easily preserved parts of their bodies. Indeed, fossil shark teeth (“tongue stones”) have been known since ancient times. The Paleozoic sharks which evolved during this time had a greater range of adaptations than exist today in sharks today since early sharks occupied ecological niches which would later be taken over by bony fish. Although these Paleozoic sharks were certainly sharks, these sharks had a number of primitive features (such as a notochord which was surrounded by vertebrae but unrestricted by them) and none have survived to this day. Some early sharks reached 4 m in length. Cartilaginous fish developed a few modifications of the braincase which are shared among all jawed fish except placoderms (such as several aspects of the structure of the otic capsule) (Maisey, 2005).

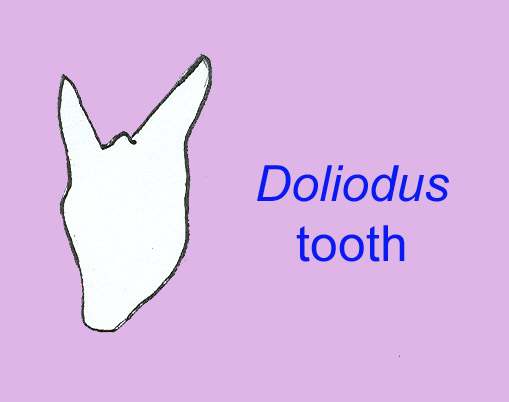

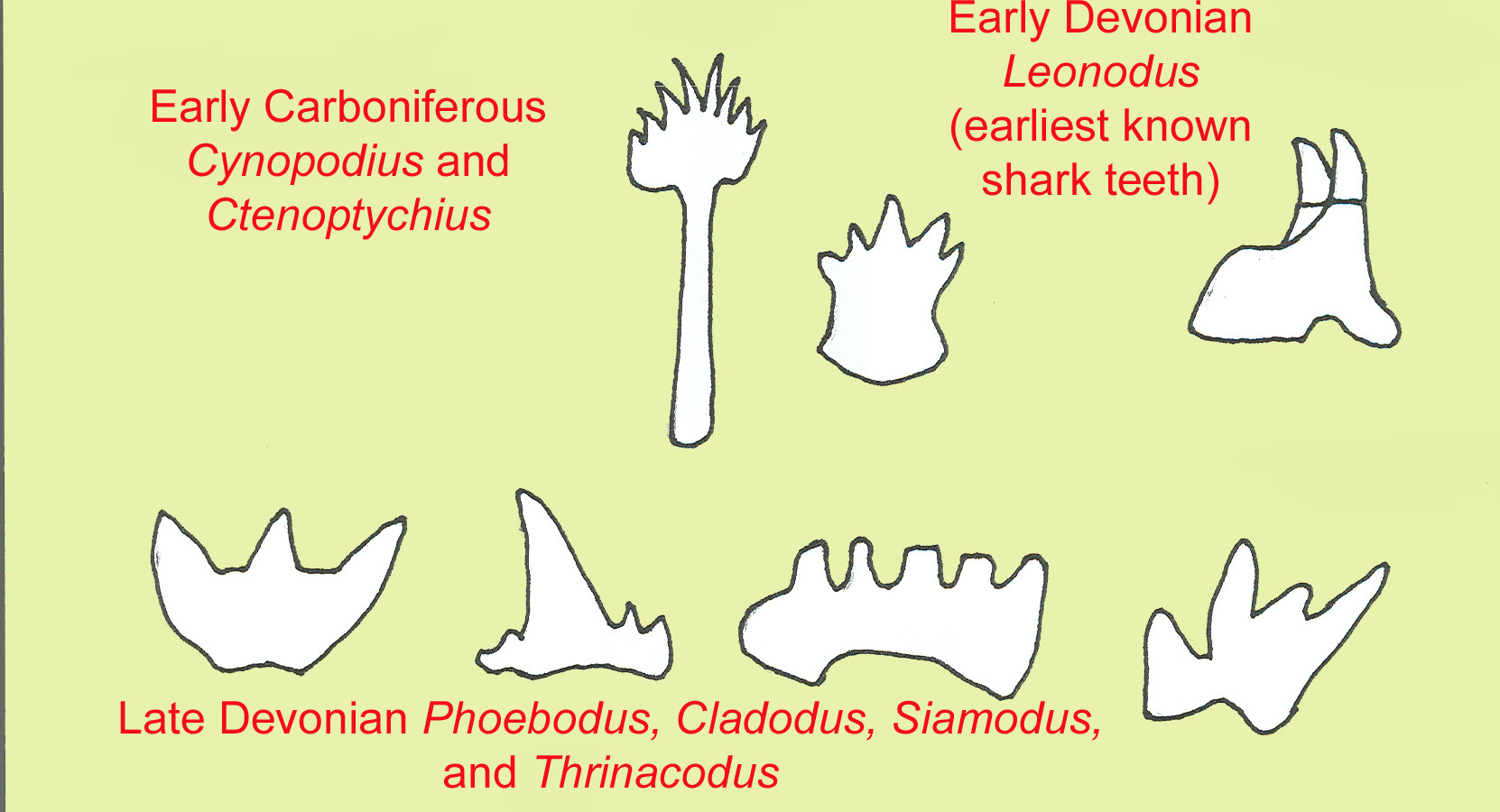

Silurian cartilaginous fish are known only from scales, a few teeth, and small disarticulated fossils (Qu, 2010). In strata dated at about 450 million years ago, there are the remains of tiny scales which are so similar to modern shark scales that they are attributed to primitive sharks. The first shark teeth are not known until strata which are 40 to 70 million years younger. Although the earliest shark-like scales are known from the Early Siluran, shark teeth are not known until later suggesting that the fish from which these scales originated may have lacked teeth or even jaws. The first fossils of true teeth are known from the shark fossil Doliodus of the Late Siluran/ Early Devonian (Long, 1995; Turner, 2004). In early shark embryos, developing teeth and denticles are essentially the same (Allen, 1999). Multi-cusped teeth of Leonodus are known from the Early Devonian (Ginter, 2004). Fossils of denticles which are slightly larger than normal denticles are known—these may be remains of the early forms of teeth. A shark may produce tens of thousands of teeth in only a few years . The teeth of early sharks are often blunted, suggesting that they were not replaced as often as those of modern sharks (Stephens, 1989; Perrinne, 1999). The first teeth of cartilaginous fish are known from the Early Devonian and measure less than 4 mm. More than 30 shark species existed by the Late Devonian. The first sharks may have originated around the southern supercontinent of Gondwana (Long, 1995).

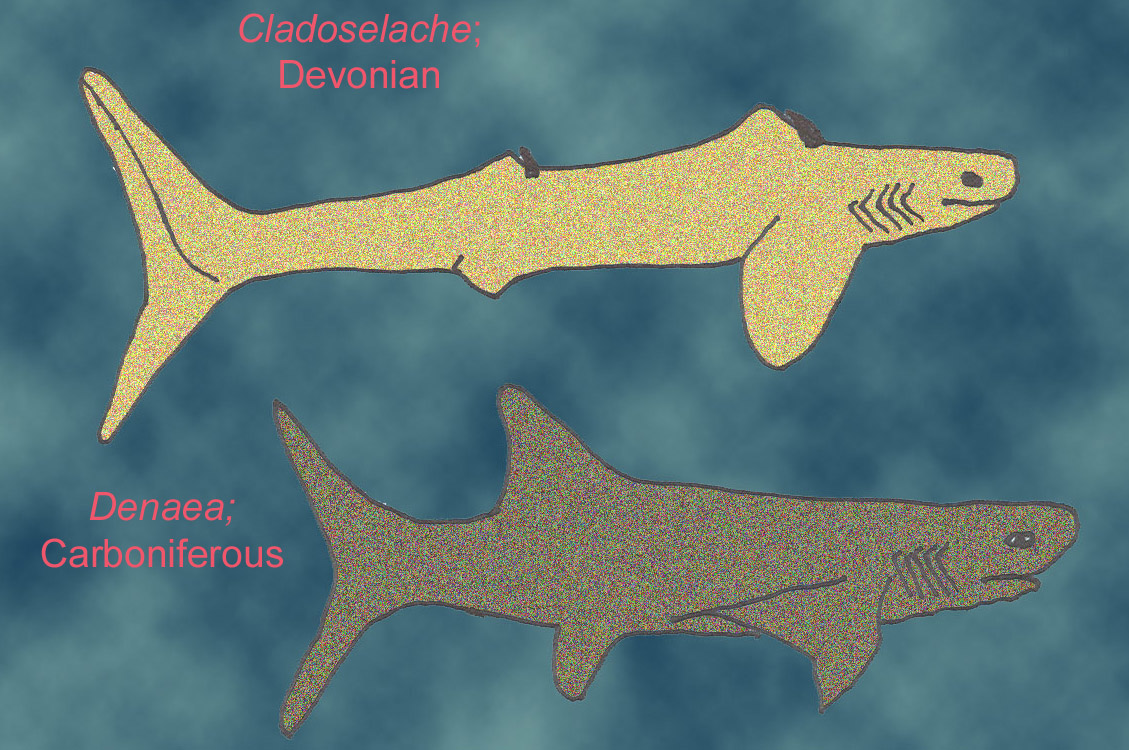

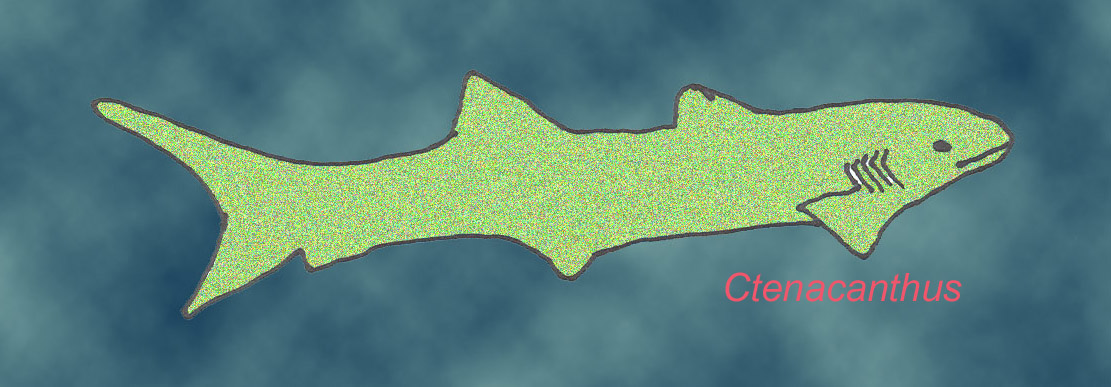

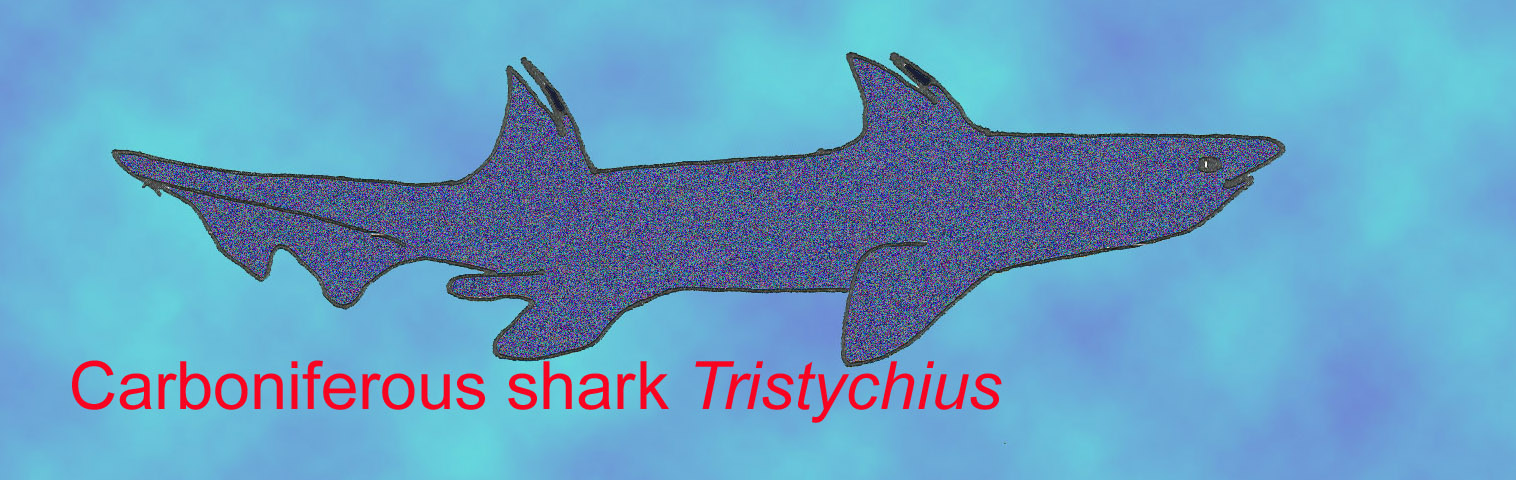

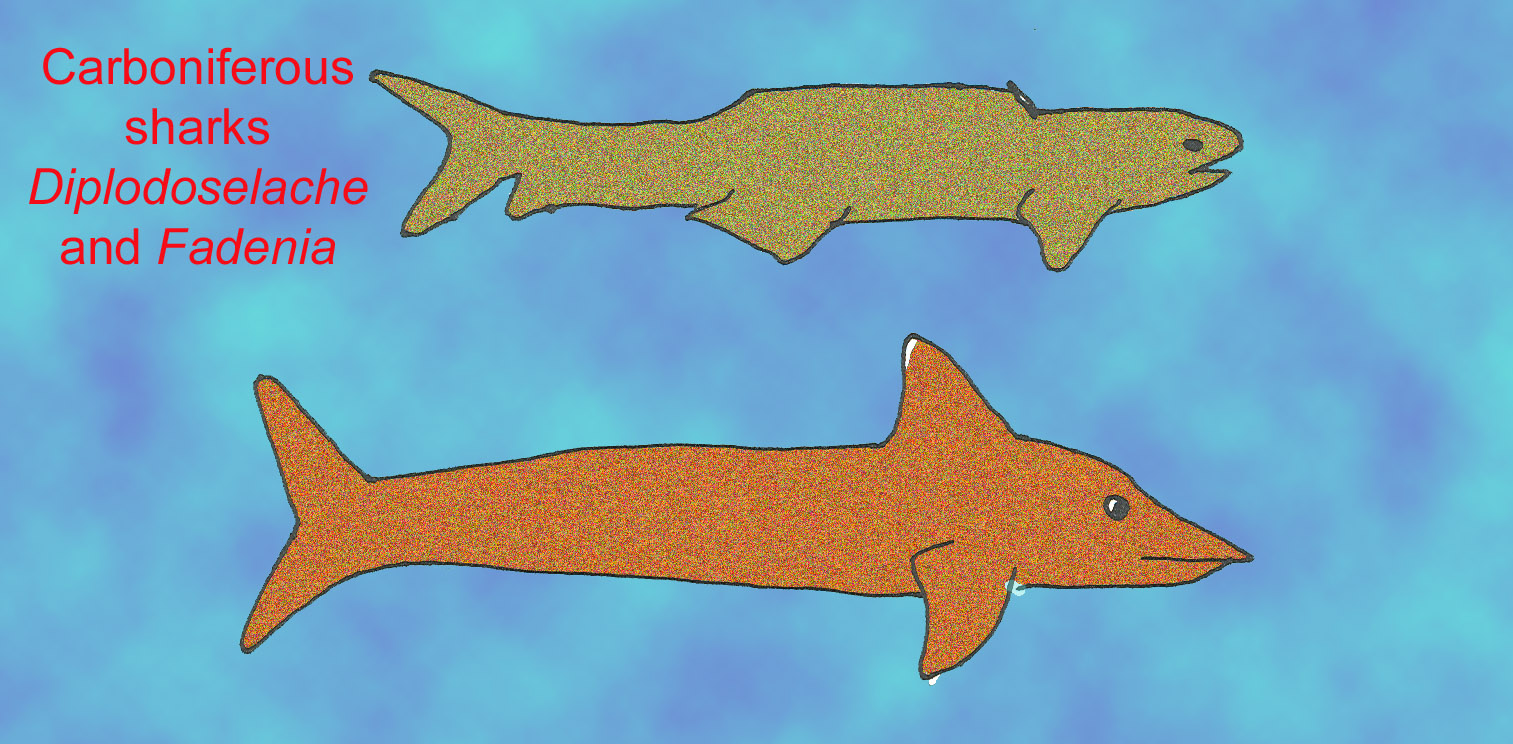

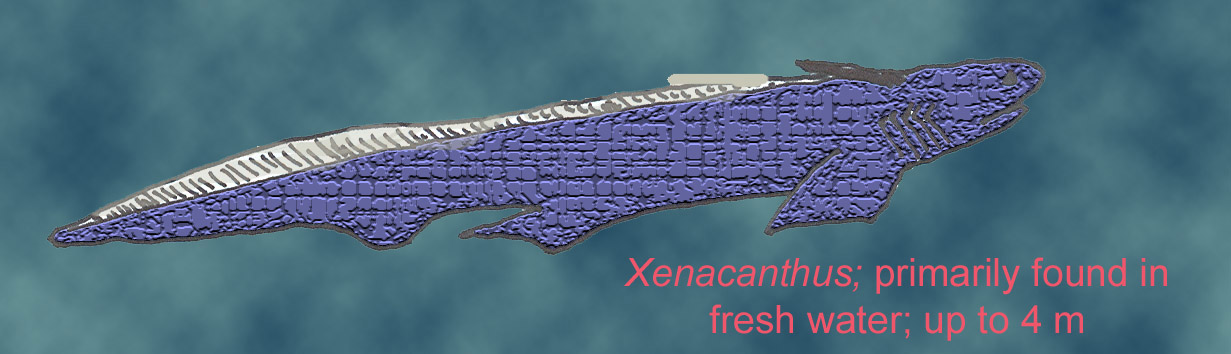

The first remains of a shark body (other than scales and teeth) date to 380 million years ago in Antarctica, Antactilamna. Around 370 million years ago several groups of sharks existed including ctenacanths (which may have been ancestral to modern sharks and the dominant Mesozoic sharks), cladodonts (which possessed multi-cusped teeth and included Cladoselache), and, shortly afterwards, the freshwater xenacanthid sharks (Perrinne, 1999). Xenacanth sharks were a dominant of primarily freshwater sharks for more than 200 million years (Stephens, 1989).

Cladoselache is known from the Late Devonian and could reach lengths of 6 feet.

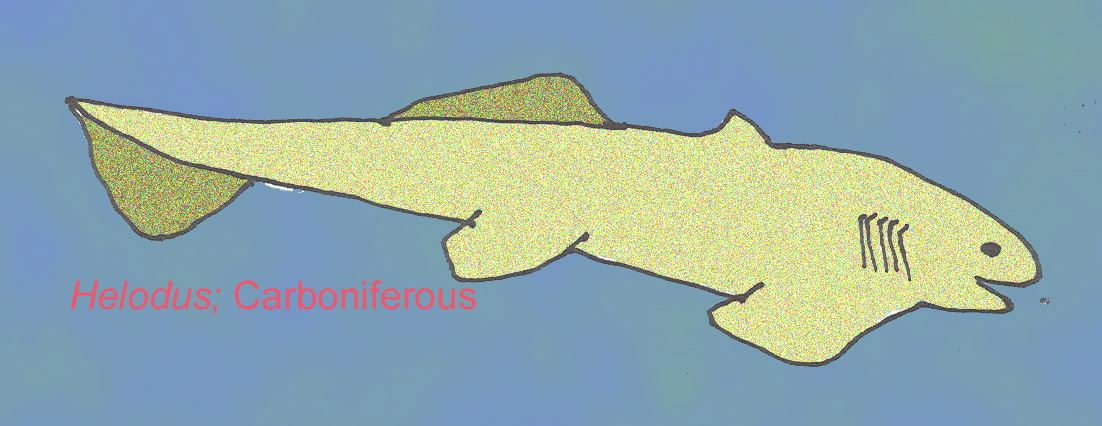

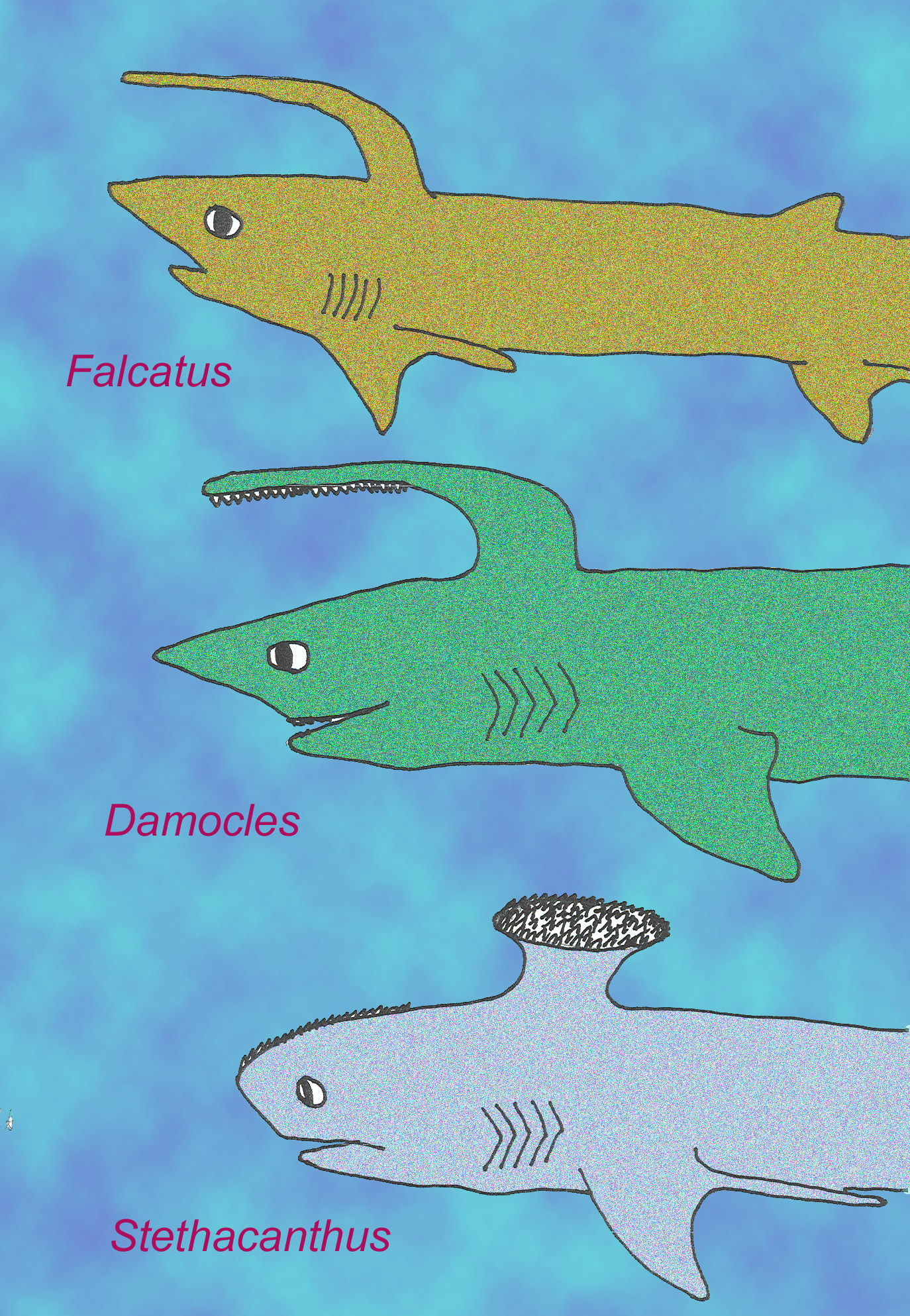

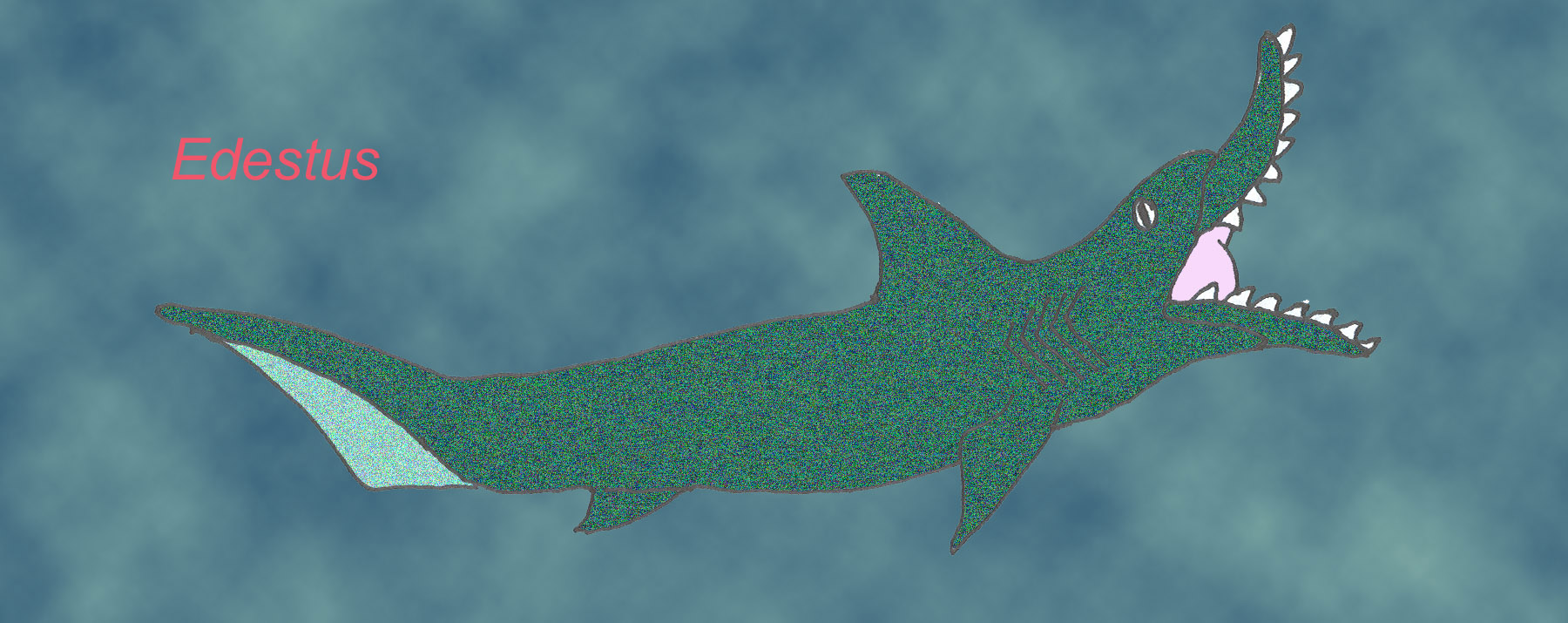

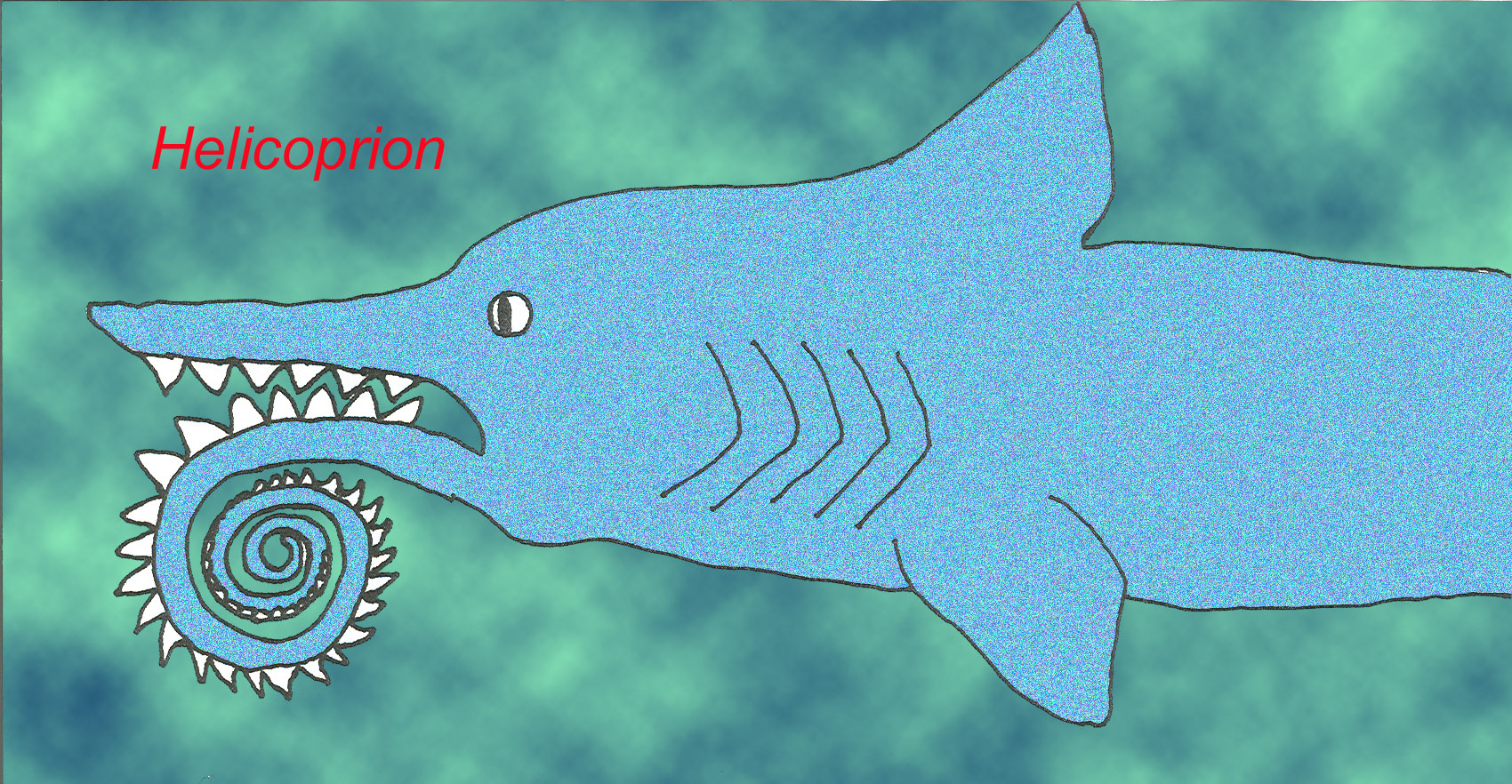

Following the extinction of the placoderms, sharks diversified in the Carboniferous. Some reached estimated sizes of 6-7 meters with meter-wide mouths. One group (which includes Stenacanthus) evolved a bony spine on their backs. Others evolved odd whorls of teeth (such as Heliocoprion) which may have helped them catch fish while swimming through schools of fish (Long, 1995).

Most early sharks are known only from their teeth. By the Late Devonian, sharks had evolved a diversity of tooth types including some with 8 cusps (compared to the two cusps of the earliest known shark teeth) (Long, 1995).

The following photos of the teeth of fossil sharks.

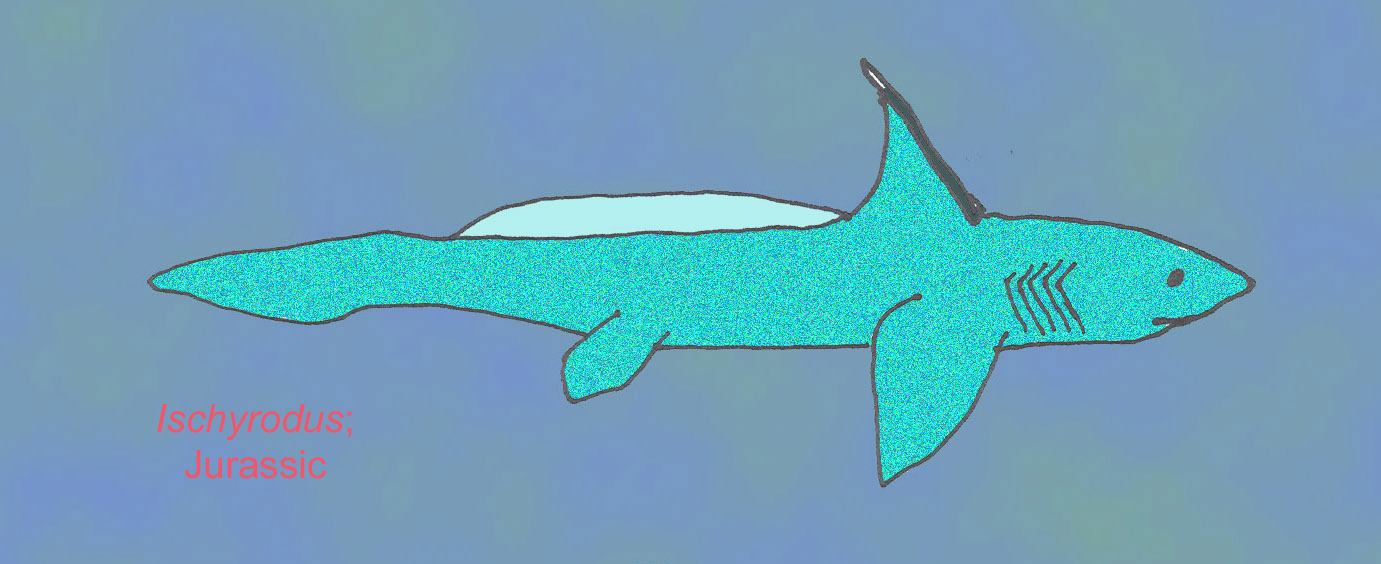

There were at least 7 major groups of Paleozoic sharks, most of that became extinct during the Permian Period. The most primitive forms lacked calcified ribs. Some had spines in their fins and others had multiple dorsal fins. All modern sharks descended form one ancestral group during the second great shark radiation in the Jurassic. In these Mesozoic sharks, the vertebral centrum was calcified and the fin spikes were reduced. They had larger nasal capsules and probably a better sense of smell (Carroll, 1988). Several advances made in the shark braincase were retained in early bony fish (Maisey, 2004).

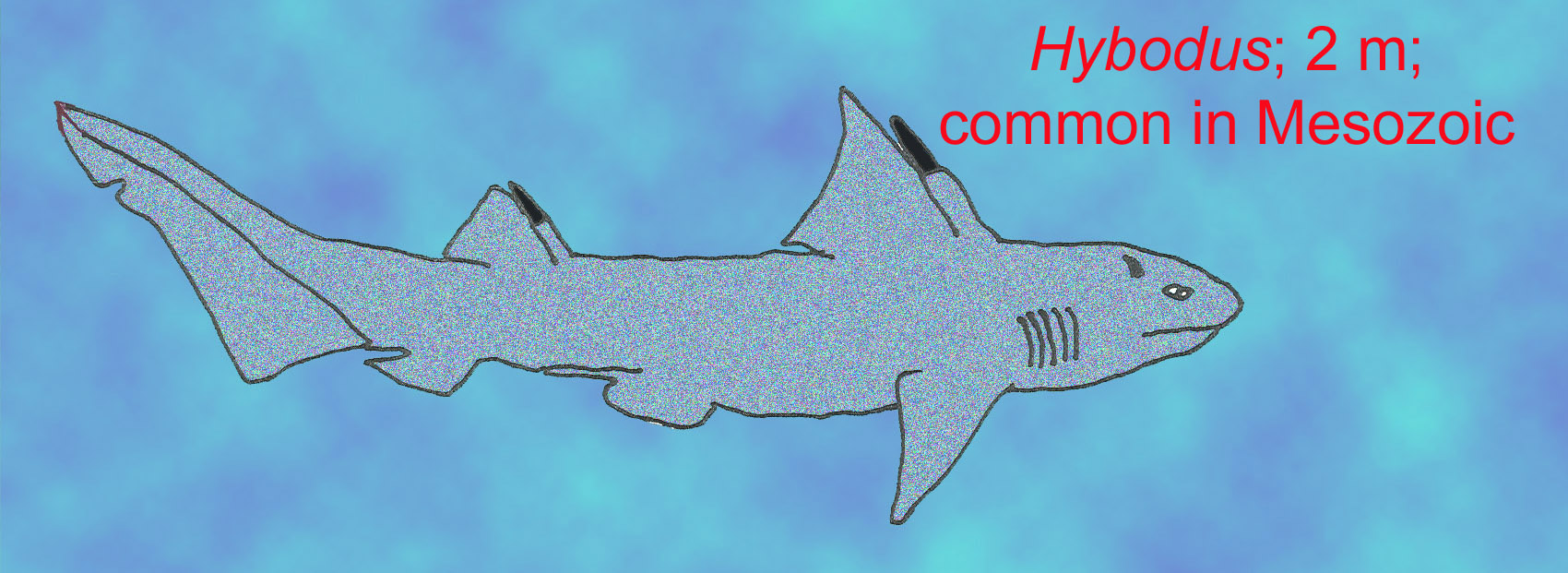

After the extinction of the placoderms, a major group of sharks diversified known as the hybodont sharks. They possessed multicusped teeth in the front of their mouths and crushing teeth in the backs of their mouths. They also possessed horn-like cephalic spines on the tops of their heads. Hybodonts are thought to be related, or perhaps even ancestral, to the first modern sharks or neoselachians which appeared at about 200 million years ago (Perrinne, 1999).

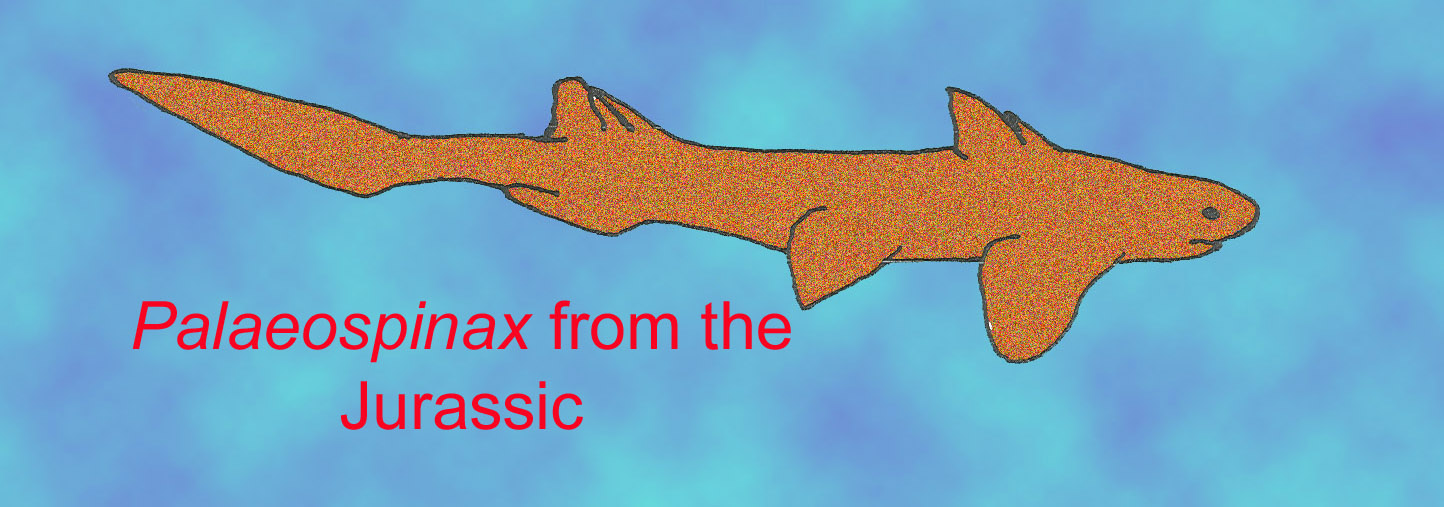

In the Early Mesozoic, one group of sharks (of which Paleospinax is a good early example) developed shorter jaws, a more ventrally positioned mouth, and a stronger vertebral column. As the mouth moved, the feeding strategy of sharks changed. Instead of swallowing prey whole in one bite, they more frequently used their teeth to cut and chop prey. Paleospinax is the earliest neoselachian with its calcified cartilage backbone (Perrinne, 1999; Moss, 1984).

Most modern groups of sharks are about 100 million years old with the oldest dating about 180 million years.

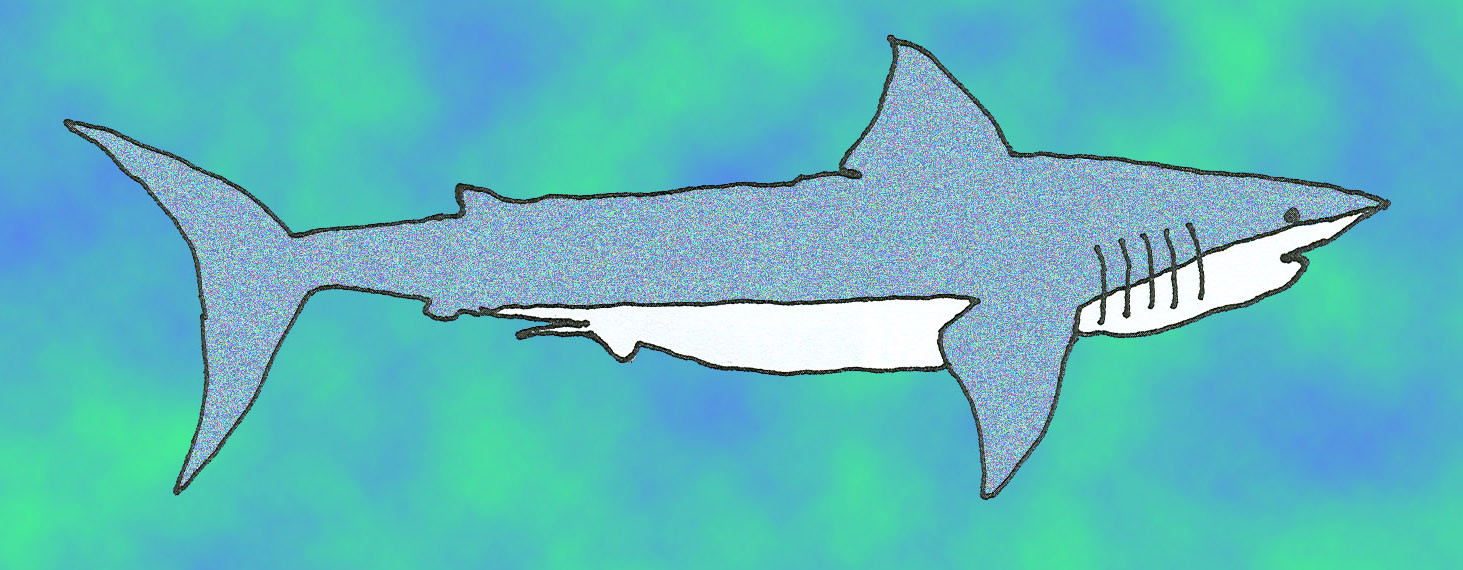

A few rare sharks (such as the megamouth shark and the goblin shark) are known since the Tertiary. A number of Mesozoic sharks reached lengths of 5-6 meters. Mako sharks from the Miocene could reach lengths of 8 meters and gave rise to modern great white sharks. The fossil shark Carcharocles megalodon lived 23 million years ago could reach lengths of 15 meters with teeth 18 cm long (twice the size of the largest great white shark ever caught). These giant sharks appeared around the time that large filter-feeding whales evolved which may have been their prey (Long, 1995). Great white shark fossils are often associated with areas which contain the fossils of primitive marine mammals (Stephens, 1989).

The fossil shark Stethacanthus is interesting because it possessed a ‘spine-brush complex’ composed of acellular bone. It also possessed a type of calcified cartilage (globular) like that of placoderms and advanced jawless fish (Coates, from Ahlberg, 2001)

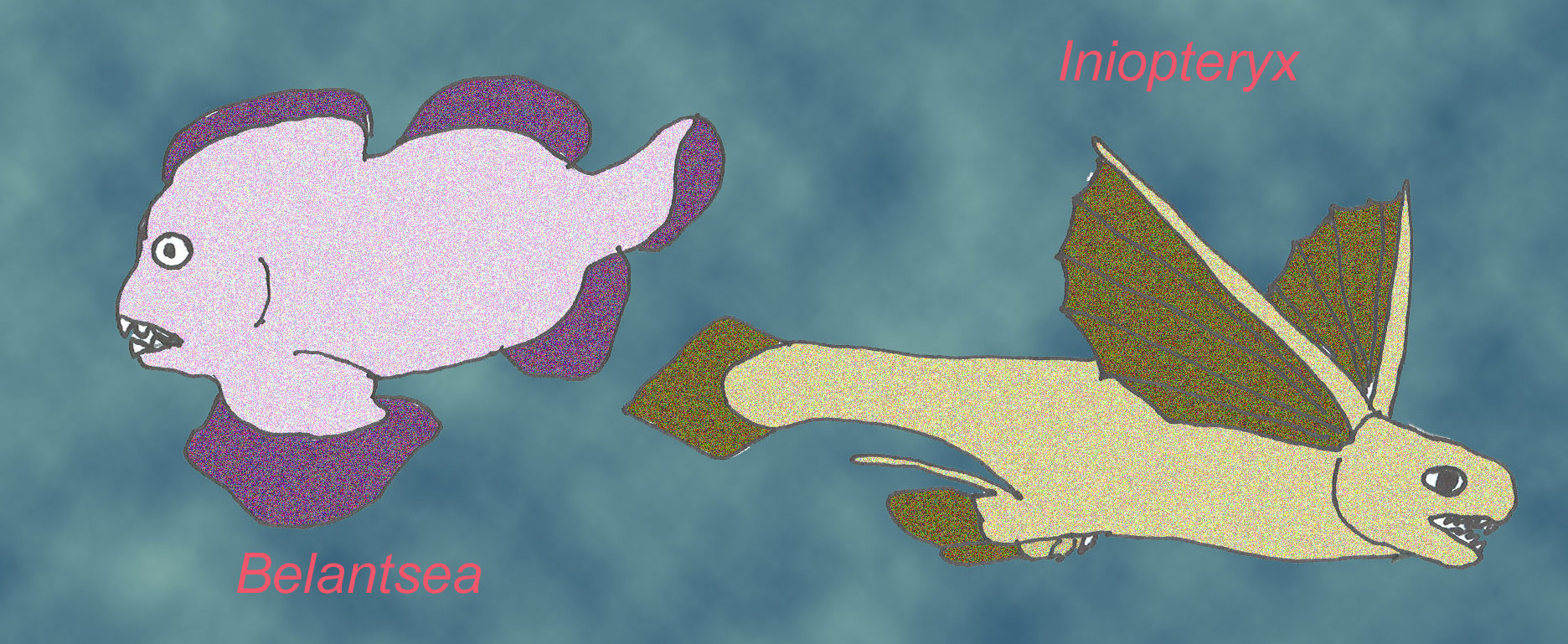

The diversity of Paleozoic sharks included some 4 to 6 inch forms whose long pectoral fins located near the top of the head might have permitted the same type of aerial gliding. Some possessed a tooth whorl and others possessed teeth on scissor-like jaws. Some possessed a bony dorsal brush and others modified dorsal spines that may have functioned in courtship (Perrinne, 1999).

. Chimeras are deep-water cartilaginous fish with large eyes that date from the Carboniferous to modern times.

Two species of the sister groups of holocephalins possessed tentacles equipped with spines ( Lund, 2004). Harpacanthus fimbriatus possessed bone or bone-like tissue in its braincase ( Lund, 2004). One modern group of cartilaginous fish includes chimeras, elephant sharks, and rabbitfish. This group diverged from shark lineages in the Devonian. The earliest fossil rays are known from the Jurassic (Long, 1995).

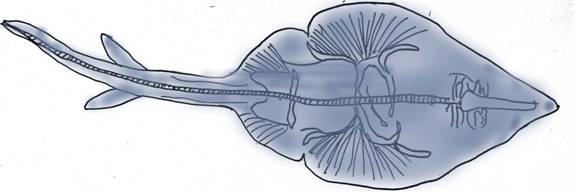

Below is a modern ray.

Other features which are present in cartilaginous fish but absent in modern jawless fish include advances in the brain and the presence of a gall bladder, urinary bladder, uterus, and reproductive ducts. Sharks differ from other fishes in having internal fertilization of gametes; claspers on the male pelvic fins allow this. Since cartilaginous fish lack the swim bladder found in later fish, sharks must swim constantly to avoid sinking.